The Placenta and the Great Pregnancy Remodel

The placenta is responsible for big changes, and risks, women face while pregnant.

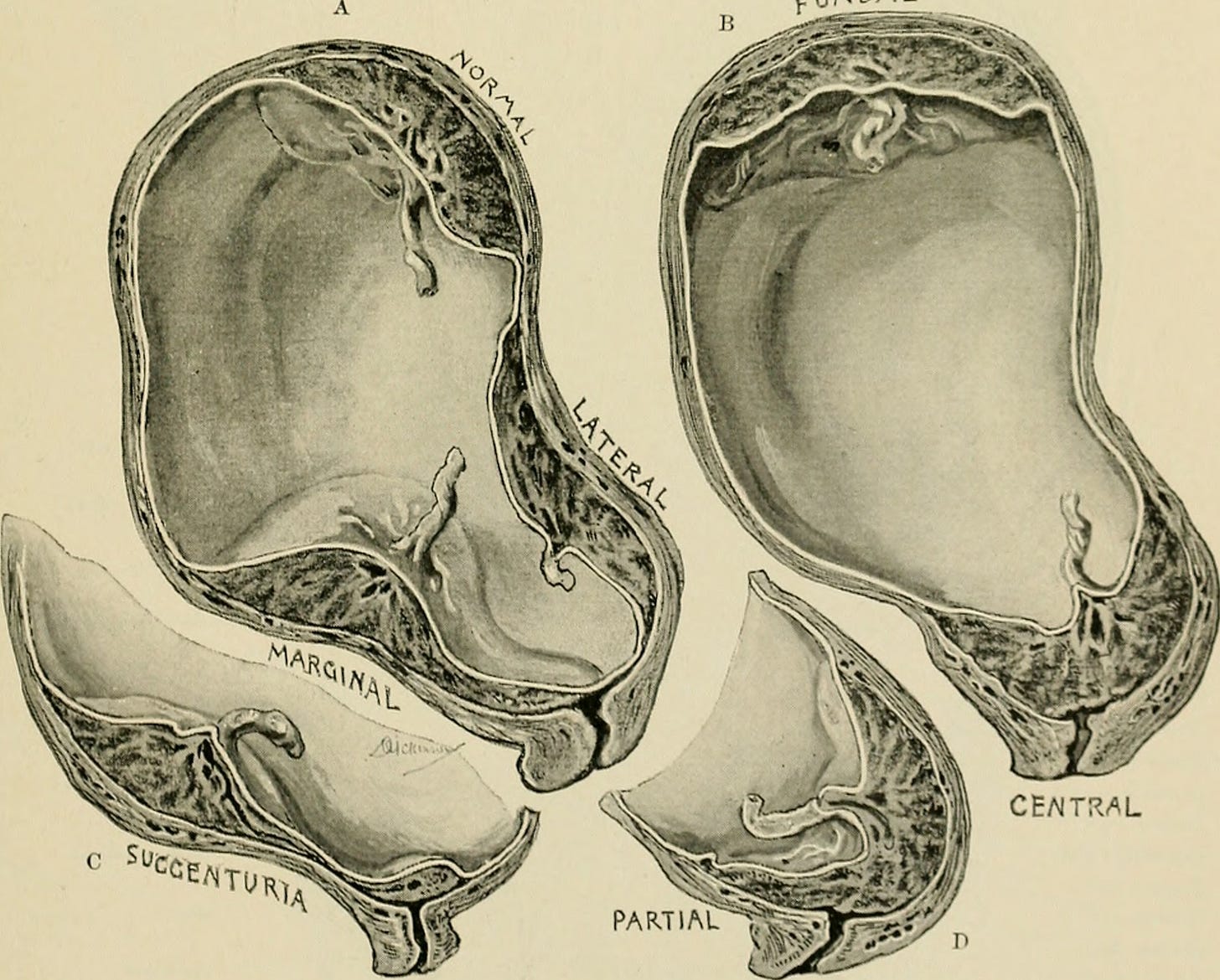

A figure from a 1903 medical textbook showing variations in placenta implantation, both normal and abnormal. Where the placenta situates in body can influence both the health of the pregnant woman and the fetus. Credit: Wikipedia Commons.

During pregnancy, a fetus is never alone. There’s the pregnant woman of course. But the two are joined by another entity and key player: the placenta.

Despite being essential to the process of pregnancy, the placenta – outside of medical settings at least – often goes overlooked. It develops from the same fertilized egg as the fetus and fuses with maternal tissue as it grows inside the uterus. But it’s commonly left out of popular figures of the stages of pregnancy and fetal development. When it is there, it’s often depicted as a sort of biological connection port, enabling the fetus, to “plug into” the woman with the umbilical cord acting as power cord.

While it’s true that one of the placenta’s key functions is to link up to the maternal circulatory system, the organ is much more than mere conduit. Its control and influence reach far beyond the uterus.

The placenta buries into the woman’s body, eroding away cell layers so it can reach her blood supply. It remodels arteries to influence blood flow – at first damming them before opening them up. It sends out hormones that affect the functioning of the rest of the pregnant woman’s organs, sometimes resulting in pregnancy-induced diseases such as gestational diabetes.

The process is all quite intrusive. It results in some significant side effects and risks. And it’s all a normal part of human pregnancy.

The rest of this piece is a high-level overview of how the placenta affects the physiology of the pregnant woman, from the earliest stages of pregnancy and onward. I hope it shows how significant a role the placenta plays in human pregnancy – and the impacts it has on women’s health and well-being.

Getting Pregnant

By the time labor and delivery come around, the placenta resembles a fleshy, veiny pancake. It’s a distinct and alien-looking form compared to the baby it’s attached to. But the placenta and the baby have shared origins: a hollow ball of cells, known as a blastocyst.

A blastocyst is one of the earliest stages of human development, forming about five days after the egg and sperm merge. While the embryo forms from a bulge inside it, the placenta arises from its exterior layer of cells.

Blastocysts are minuscule. Made up of only a couple hundred cells, they’re about as wide as a human hair. So, when one arrives in a woman’s uterus a few days after fertilization occurs, it takes a special signal to inform her body that it is now pregnant.

The placental cells are responsible for ringing that alarm. They do it by releasing a powerful hormone called human chorionic gonadotropin, or hCG.

hCG is the pregnancy hormone. It tells the ovaries to maintain the uterine lining instead of sending its own chemical signals that tell the lining to slough off. For a woman with a regular menstrual cycle, this missed period will usually serve as the first sign of pregnancy. If she takes a pregnancy test to confirm her suspicions, hCG is the molecule the test was designed to detect.

hCG is also thought to be connected to another early sign of pregnancy: morning sickness. About 70% of women experience morning sickness, which causes varying degrees of nausea and vomiting, and despite the name, can strike at any hour of the day. Higher levels of hCG are associated with more severe symptoms, with a 2002 study finding that morning sickness is the second most common pregnancy-related reason women are hospitalized. (The first is pre-term labor).

While some scientists have tried to frame morning sickness as a potential evolutionary adaptation that may have kept the ancestors of today’s humans from eating rancid food, the condition might just be an unfortunate case of hormonal imbalance, as placenta researchers Michael L. Power and Jay Schulkin explore in their book The Evolution of the Human Placenta. As the woman’s hCG levels spike, it can bind to receptors on the gland and overstimulate it, triggering morning sickness symptoms.

Morning sickness subsides when hCG levels decrease, which usually happens by the second trimester. But placenta keeps a detectable level of the hormone flowing until labor to keep the uterine lining intact and the pregnancy in place. With the pregnancy established and the blastocyst settled into the uterine lining, the next step for placental cells is to start looking for the blood that delivers the nutrients that fuel fetal growth.

Bring on the Blood

In some mammals, the placenta keeps some distance between itself and the maternal blood supply. In these situations, maternal blood and placental cells never directly meet. Nutrients and waste are exchanged through layers of cells.

But that’s not the case for humans.

For us, the placenta is in direct contact with the blood of the pregnant woman. By nine months it’s absolutely bathing in it, with about 700 milliliters of blood passing through the placenta each minute. That’s just under a bottle of wine’s worth of blood if you want an image that will stick you!

To provide all that blood without passing out or worse, women in the later stages of pregnancy produce 30% more blood than women who aren’t pregnant. Hormones released by the placenta likely play a role in signaling the pregnant woman’s body to make more blood.

But how does the placenta get all that blood flowing to it the first place? It sends out a specialized squadron of cells that move independently instead of growing together as a tissue. This squadron erodes away the cellular layer that separates the placenta from the spiral arteries – which provide blood to the uterine lining and have a distinctive spring-like shape that grows in response to the thickness of the uterine lining.

But the placental cell squadron doesn’t stop there. Some of the cells enter the arteries where they influence blood flow over the course of the pregnancy.

During the first trimester, they glom together to plug up the arteries. The reduced blood flow helps keep the embryo away from oxygen, which could damage its DNA at this early stage of development. In the meantime, the embryo gets all the nutrients it needs from a yolk sac.

By the second trimester, the placental cells open the arteries up. They line the inside of the arteries and mesh into the artery walls, removing collagen and smooth muscle cells that help maintain its tubular shape. The end result is an artery that resembles a windsock. The dilated mouth helps increase the volume of blood delivered to the placenta while keeping the pressure it hits the tissue relatively low.

The dots represent various types of placental cells that make up the “cell squadron” that’s described above that remodels the spiral arteries of the pregnant woman. Credit: R. Pijenborg et al 2006.

Big Brains for Babies, Bleeding Risks for Women

Humans are special among placental mammals for having a particularly invasive placenta that grows deep into the uterine lining.

Some scientists have suggested that our invasive placenta may have helped bring about our big brains, which do a lot of developing in utero. At birth, a baby’s head makes up about 25% of its body length and the brain inside is about the size of an adult chimpanzee’s. A major role of the placenta is delivering the resources the brain needs to accomplish that impressive growth in just 40 weeks’ time.

However, other placental mammals complicate the theory that placenta invasiveness helps deliver those resources, as Power and Schulkin explain in their book. Guinea pigs have placentas that invade even more deeply than humans and they don’t seem that brainy. Dolphins have big brains but have placentas that never directly tap the maternal blood supply. What’s more, the authors say that research is inconclusive when it comes to connecting placental invasiveness to increased nutrient flow.

Whether it’s a prerequisite for human brain development or not, the invasiveness of the human placenta matters to women. That’s because it can lead to placenta overgrowth, a condition called placenta accreta. Most cases involved the placenta growing too deeply into the uterine lining. In the most severe cases, it can grow through the uterine muscle and attach to other organs such as the bladder, rectum, or intestines.

A diagram showing degrees of placental growth and overgrowth. The percentages refer to the frequency of different degrees of placenta accreta. More severe stages of overgrowth are known as placenta increta and placenta percreta. Credit: Wikipedia Commons.

The biggest concern of placenta accreta is bleeding. The overgrowth of the placenta can prevent the organ from cleanly detaching after birth, which can interfere with the closure of the spiral arteries. In their dilated state – itself the result of remodeling by placental cells – the open arteries lead to massive hemorrhaging. In cases where the placenta grew outside the uterus, the woman may face tissue damage to other organs where the placenta implanted.

Rather than having the pregnant woman risk a life-threatening big bleed, if placenta accreta is discovered before birth1, the consensus approach, according to the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists, is for women to undergo a hysterectomy while having a cesarian section delivery. While this prevents massive bleeding by leaving the placenta intact and attached, it also leaves women without a uterus – a pretty significant intervention with a host of potential health consequences, aside from ending the capacity to bear children. It’s not a decision that is made lightly, though. Stopping hemorrhage associated with placenta accreta is the most common reason for emergency hysterectomy.

Worryingly, cases of placenta accreta are on the rise in the United States. Rates have quadrupled since the 1980s, according to the National Accreta Foundation. And according to a 2016 study, the rate of placenta accreta was 1 in 272 women who were discharged from the hospital with a birth-related incident.2 This increase is linked with the rise in of cesarean section deliveries, which cause uterine scarring associated with placenta accreta in future pregnancies. The risk of a woman experiencing placenta accreta increases with each cesarian.3

Despite the risks it can bring the pregnant woman, our invasive placenta enables the organ to be awash in maternal blood. This enables exchange of materials between the maternal and fetal circulatory systems – with hormones, nutrients, gasses, and other cellular products passing between the two.

But the placenta is more than an intermediary. It sends signals of its own. They enable the placenta to exert influence on the pregnant woman’s body far beyond the uterus. What starts with GnH, the hormone that tells the body it’s pregnant, grows in scope and influence as a pregnancy progresses.

Hormone Hub

The late Samuel Yen, a reproductive endocrinologist and medical doctor, referred to the placenta as the “third brain.” The evocative nickname was a nod to the placenta’s biochemical orchestration abilities and the myriad of hormones the organ secretes, which influence both fetus and pregnant woman.

The hormones cover a range of categories and classes. And figuring out exactly what they do is an active field of research. But the bottom line is they make pregnancy a total body process for the woman.

As this chart from a 2018 paper on placental hormones shows, there’s not a major organ system that is unaffected by pregnancy. As the authors write: “maternal adaptations to pregnancy are largely mediated by the placenta.”

Figure from T.Napso et al 2018

By staying in constant contact with both the maternal and fetal bloodstream, the placenta can adjust and modulate hormone levels. Women are subject to their effects.

To me, one of the most illustrative examples of the placenta’s influence is the loss in bone density that many women experience during pregnancy. The placenta is a major source of a hormone that strips away calcium from maternal bones and releases them into the maternal bloodstream. The calcium ions are then put to use building up the fetal skeleton.4

Another good example is gestational diabetes, in which placental hormones interfere with the efficacy of insulin produced by the pregnant woman. It affects 2-10% of pregnancies in the United States, according to the Center for Disease Control. Although the condition resolves after giving birth, it’s associated with women going on to develop type 2 diabetes. That’s not to mention the other risks the condition can cause during pregnancy itself.

Coming to Terms

There’s a popular anti-choice meme that scoffs at the notion of “My body, my choice” by labeling a drawing of a pregnant woman with the words “your body” and the fetus inside her with the words “not your body.”

Unsurprisingly, it doesn’t consider the placenta. Once you do, arguing for clear boundaries during pregnancy sounds ridiculous. An embryo contained in a laid egg, such as a platypus or crocodile, has boundaries. An embryo or fetus that is connected to a woman through an organ that can strip away her bone and remodel her arteries very much does not.

As placental mammals, there’s no way we can avoid the placenta’s influence on pregnancy. But in discussions and policy around women’s reproductive health, rights, and experiences, we can start to acknowledge it.

While biology puts the placenta in the driver’s seat during pregnancy, it’s up to society to give women back some control. We can do that with providing medical and social support during pregnancy, and the option and resources to safely end it.

The National Accreta Foundation said that it was 1 in 272 pregnancies, not pregnancies that included a birth-related incident. But I believe that’s probably a misreading of the 2016 study, which it cites on its website.

I want to emphasize here that cesarean delivery is a life-saving intervention. However, it is important to recognize its connection to placenta accreta and for women and their doctor’s to take that into account when creating birth and delivery plans.

Women are able to fortify their skeletons again after giving birth, although breastfeeding is another draw on calcium from bones. Interestingly, breastfeeding may help improve bone density of in the long run, according to a 2014 study – although the authors note it's far from a clear picture.